“How Your Zip Code Could Shape Your College Future: A Look at Income Inequality Close to Campus”

Michael Burns

Staff Reporter

9/19/2024

Imagine two students growing up just a few miles apart but living in completely different worlds. In one neighborhood, families enjoy stable incomes, well-maintained homes, and access to highly resourced schools.In the other, families struggle to make ends meet, schools fight for funding, and educational opportunities are limited by the local economy. The students might share the same dreams, but the zip code they were born into may ultimately determine their future. In North Central Massachusetts, the contrast between the 01420 and 01462 zip codes provides a clear case study of how income inequality plays out in our education system. The effects of this economic divide go far beyond test scores, creating long-lasting disparities that shape students’ access to higher education, career opportunities, and lifetime earning potential.

Professor Christa Marr, an associate professor of Economics at Fitchburg State University, emphasized the importance of education in breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty. “Education is the main means of intergenerational mobility,” Marr said. “But the persistence of income between generations is fairly large, meaning that the opportunity pathway is narrow. We don’t see access to education among lower-income families as often as we should.”

Marr explained that “poverty traps” — systemic barriers preventing low-income students from advancing beyond high school — play a significant role in limiting educational access. “There certainly are poverty traps that exist,” she said. “Whether the cause is the cost of education or other systemic barriers, it’s clear that many students from lower-income families do not have the same educational opportunities as those from higher-income backgrounds.”

These observations reinforce the data from Fitchburg and Lunenburg. While wealthier communities have greater financial resources to support students, low-income areas like Fitchburg are more likely to see students struggle with housing instability and underfunded schools, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage.

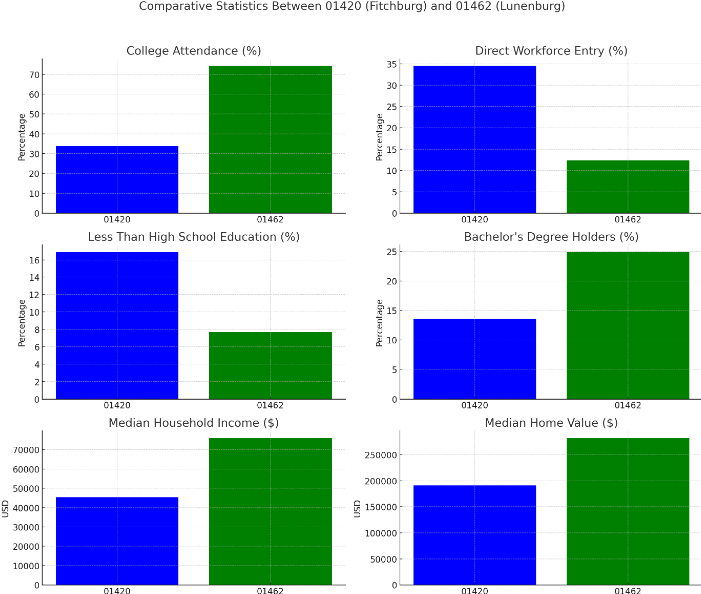

The disparities in income and education between these two ZIP codes are not unique, but they offer a stark illustration of how ZIP codes can define futures. In 01420, only 33.7% of students attend college, whether private or public, and 34.5% enter directly into the workforce, while a staggering 74% of students in 01462 pursue higher education, and 12% go directly into the workforce, according to the 2022-23 Plans of High School Graduates Report from the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DOE).

These differences are not merely statistical; they define the opportunities available to young people and how their futures are shaped from early childhood through high school.

In 01420, the city of Fitchburg, the median household income is $45,363, and the median home value is around $191,100. Many families in this area struggle with housing instability, as only 37% of households own homes with a mortgage, and 41% of households are renter-occupied, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The economic challenges of this community are further reflected in the educational attainment levels: 16.9% of residents have less than a high school diploma, and only 13.6% hold a bachelor’s degree, according to the 2020 Census from the U.S. Census Bureau. These statistics point to a community where financial pressures affect educational outcomes, and the lack of wealth accumulation through homeownership limits long-term stability and investment in local schools.

Contrast this with 01462, Lunenburg, where the median household income is $76,063, and the median home value is $282,100. Here, 61% of households own homes with a mortgage, and only 1% of households are renter-occupied.6 The higher levels of financial security mean that students are more likely to come from stable homes with parents who can invest in their education in both high-school and beyond. The education levels in this community reflect that stability: only 7.7% of residents have less than a high school diploma, while 24.9% hold a bachelor’s degree, and 9.5% have a master’s degree. This creates a much stronger foundation for academic success from early childhood, reinforced by the availability of educational resources and extracurricular activities.

While Massachusetts has programs like METCO that allow students from lower-income districts to attend schools in wealthier areas, Marr noted that the access is limited.

“There’s a lot of murky middle ground . . . where not all students are able to benefit from these programs, and that’s a problem,” said Marr. “In wealthier areas, you have access to more experienced teachers, better programs for different types of learners…But in lower-income areas, the lack of funding means these kinds of resources are scarce, creating even more inequities.”

Schools in 01462 benefit from higher property tax revenues, which leads to better facilities, more experienced teachers, and enriched learning programs. Students in the Lunenburg district are more likely to have access to advanced placement courses, extracurricular activities, and college counseling, all of which provide them with a head start. Meanwhile, schools in the Fitchburg district face significant funding challenges, resulting in larger class sizes, fewer academic opportunities, and limited extracurricular options.

These disparities create a cycle in which high-income students continue to perform better due to their learning environments, while low-income students face greater barriers to success. The academic achievement gap that emerges from this is not simply about individual effort or talent. Instead, it is deeply tied to the unequal distribution of educational resources based on where a student lives. Children in wealthier districts are set up to succeed, while those in lower-income districts struggle to catch up.

The consequences of income segregation are stark. High-income, predominantly white students are afforded every opportunity to excel academically, setting them on a trajectory for success in college and beyond. The SAT scores further demonstrate this divide, with students in 01462 scoring over 100 points higher on both reading/writing and math sections than those in 01420. Meanwhile, students in low-income areas are left to navigate an education system that is not equipped to meet their needs, leaving them at a distinct disadvantage from the start. The achievement gap is not just a reflection of academic ability but a manifestation of the broader inequalities that shape the distribution of resources and opportunities within our education system.

The rising cost of higher education has transformed college from an opportunity for upward social and economic mobility into a gatekeeper that separates students based on their financial backgrounds. For students in lower-income areas, the cost of tuition, housing, and related expenses often makes college seem like an unattainable goal. Financial barriers such as insufficient aid, reliance on student loans, and the burden of balancing work with studies mean that many low-income students face limited options for pursuing a degree.

In contrast, students in wealthier districts disproportionately benefit from greater financial security, allowing them to access higher education with fewer obstacles. With families more able to cover the cost of college tuition and living expenses, students from these high-income households are not only more likely to attend college but also to graduate without the same level of debt or financial strain. This perpetuates a cycle of inequality where education becomes a tool that reinforces socio-economic divides rather than a pathway to positive economic mobility .

Marr explained how the social factors also play into students concerns when it comes to pursuing higher education.

“At Fitchburg State, some of our focuses are on looking at how to acclimate students to a college environment. I think one of the biggest things that I see in my research is creating Mentors or sort of having aspirations. One thing that our new president said that she’s doing which I found really attractive was to have a recruitment office in Fitchburg High School. I think having students see a visible stand for Fitchburg State University within their High School creates that idea that this Fitchburg state is for me.”

She also emphasized that financial aid alone is not enough.

“There’s always a trade-off when it comes to the cost of higher education, but it’s more than just the money,” she explained. “It’s about breaking down mental barriers, helping students see themselves as capable of succeeding in a university setting.”

Higher education is a major determinant of future earning potential, with college graduates consistently earning more over their lifetimes than those without degrees. The divide between those who can afford college and those who cannot further widens income inequality, as wealthier students gain access to better jobs and higher salaries, while low-income students struggle to compete in the same market. The average earnings for 2010 graduates can demonstrate how students from 01420 earn significantly less ($50,544) than those from 01462 ($77,352) over a 12 year stretch.

The barriers to college completion not only limit a student’s individual economic pursuits, but also contributions to the long-term economic stagnation of their community. Without access to higher education, these students are more likely to remain in lower-paying jobs, further rooting the economic disadvantages of their area.

Marr also raised the issue of “brain drain,” a common challenge for communities of regional comprehensive institutes . “Even if we manage to get students from Fitchburg to pursue higher education, we often see them leaving for higher-paying jobs in places like Boston or Worcester,” she said. “So while we might create a pathway for them to get a degree, if they don’t come back to their community, we’re not seeing the full benefit.”

The phenomenon of brain drain that Marr highlighted has a direct impact on the long-term economic health of communities like Fitchburg. When students pursue higher education but move to urban centers for better job opportunities, they fail to reinvest their skills and income back into the local economy. This loss of talent means that Fitchburg, despite producing college-educated individuals, doesn’t reap the benefits of their contributions. Without these graduates returning to start businesses, engage in civic leadership, or bring new skills to local industries, the community struggles to grow economically. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: the students who leave for better opportunities elsewhere don’t help lift Fitchburg, and in turn, the town remains less attractive to the next generation of graduates. As Professor Marr pointed out, initiatives like the BF Brown building redevelopment and investment into the theater block and north Main street show promise in reversing this trend, but there is still much to be done to ensure that Fitchburg retains its homegrown talent and secures a path to revitalization

To address this growing divide, policies that reduce the financial barriers to higher education are essential. Increased financial aid, reduced tuition costs, and targeted support for low-income students could help level the playing field, ensuring that education serves as a bridge to opportunity rather than a wall that divides the “haves” from the “have-nots.” Without these interventions, the gap between wealthy and low-income students—and their communities—will continue to widen.

Income segregation and unequal access to education are not simply the result of individual merit or effort; they are deeply rooted in structural forces that shape the geography and economy of school districts. From housing markets to zoning laws to public policy decisions, systemic economic factors play a powerful role in determining which communities thrive and which struggle. The fact that 72.6% of students from the 01420 school districts are low-income compared to only 24.7% in 01462 points to the structural challenges faced by students in poorer districts.

The housing market is a primary driver of this inequality. High-income families can afford homes where property values are higher and public schools are better funded through local taxes. Zoning laws further reinforce this segregation by creating barriers that prevent lower-income families from moving into these more desirable neighborhoods. Policies that restrict the development of affordable housing or limit the diversity of housing options make it difficult for families in lower income neighborhoods to access the same educational resources and opportunities. This systematic disparity ensures that the cycle of poverty continues, with little opportunity for upward mobility.

These patterns reveal how income inequality and segregation are maintained through institutional forces that favor the wealthy. The benefits of living in affluent districts are not confined to the current generation but are transferred to future generations, deepening the divide between high-income and low-income families. Without addressing the structural roots of this inequality, the gap between communities like 01420 and 01462 will only widen, making it more difficult to create a fair and equitable education system. Breaking this cycle requires policy interventions aimed at reducing income segregation and equalizing educational opportunities.

To address these disparities, a multifaceted approach is necessary. First, increasing funding for schools in low-income districts is essential. Equitable funding will help ensure that students have access to quality teachers, smaller class sizes, and extracurricular opportunities that are critical to academic success. Second, policies that make higher education more affordable must be prioritized. Increasing need-based financial aid and reducing tuition costs for low-income students would enable more students to pursue higher education, breaking the financial barriers that currently divide access to college along economic lines.